Cultural Appreciation

The below was published in Nikkei Asia here in December 2021.

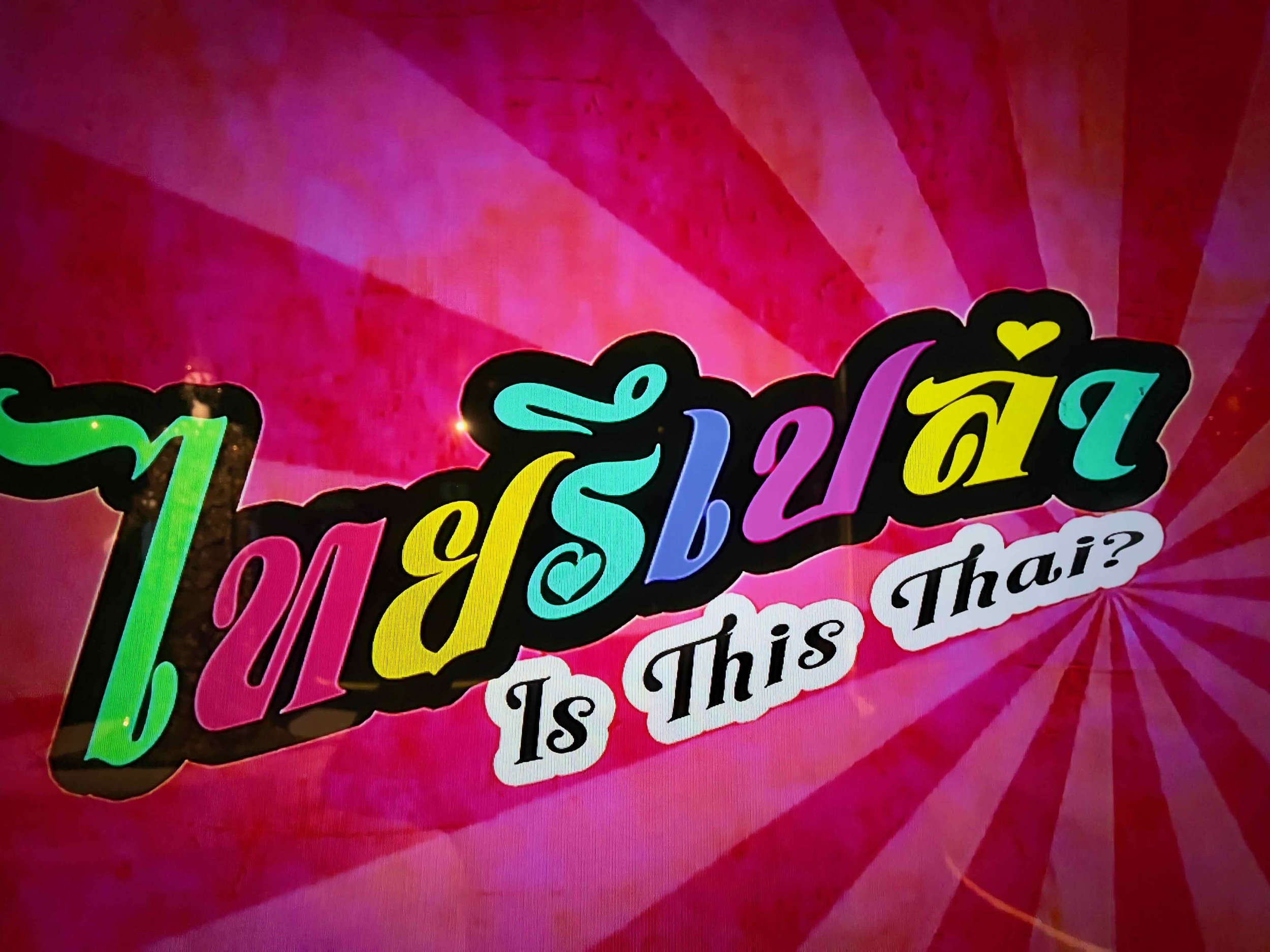

A giant electronic screen demanded, “But are they really Thai?” in front of an exhibition of some of the country’s most recognizable cultural icons. It was not what I expected to see on entering Bangkok's Museum Siam, given that national museums usually focus on emphasizing their country’s uniqueness as opposed to questioning it. So this definitely warranted a closer look.

The displays inside would certainly give ardent nationalists pause for thought. They began with pad thai, one of the country's best-known dishes, a delicious concoction of sautéed noodles with a salty-sugary kick, and a culinary icon in a country that’s obsessed with food. But the display pointed out that it had actually originated as a Chinese import. It was then given a few tweaks by Thailand's military government in the 1930s, removing the pricey pork and adding egg and fish sauce for example, before being marketed as a national dish with the goal of getting people to switch from eating rice during a time of shortages.

After digesting that, it was on to Thai massage, a vigorous kneading, twisting and hammering of the body that aims to revitalize the energy meridians. It's a therapy proudly celebrated in Thai culture, and a world away from the oily rubdown that passes for massage in most of the rest of the world. But, as the museum now explained to me, its roots in fact lie in a system invented by a doctor in India a couple of millennia ago that was imported into Thailand along with Buddhism.

Next in line were tuk-tuks. I had always thought of these as a quintessentially Thai mode of transport, doubtless invented on the busy streets of Bangkok. But it turned out this three-wheeled love child of a motorcycle and a pickup truck was actually brought to Thailand from Japan in the 1960s, where it had been known as the Daihatsu Midget. The Japanese themselves had in turn pinched it from the Italians in the 1950s, where it was originally conceived as the Piaggio Ape shortly after World War II.

Thai traditional dress didn't escape scrutiny either. I discovered that the first Thai lace blouses, today eponymous with traditional formal wear, were introduced in the early 1900s after King Rama V visited Europe and took a liking to the style favored by Victorian ladies. Likewise, gentlemen's chong kraben trousers and traditional jackets were adapted from a design that originally came from India.

And on it went. I learned about overseas influences in the design of the national flag (the blue band representing the monarchy was apparently first proposed by a foreigner), that the mythical Garuda bird on the royal seal originated in India, and that the Tourism Authority of Thailand's logo was designed by an American. All of this was explained to me within the confines of a beautiful old museum building, formerly the Ministry of Commerce, that it turned out had been designed by an Italian.

The question was whether such foreign roots made any of the cultural icons on show somehow less Thai or unique? I had to say no. In each case, the gem in question had been customised and seasoned with some local magic - "we always added a little spice" as the museum curator put it - resulting in fresh new creations that were very distinctly Thai.

What was not unique, however, was the practice of undertaking such cultural borrowing in the first place, a beautiful and inevitable result of our incessant human movement and interaction over the centuries. The same kind of exhibition could be staged anywhere in the world and would likewise reveal the local culture as a magpie's nest, stuffed full of trinkets from far and wide.

Take the U.K. for example, where I was brought up. Our local language is a mishmash drawn from all over Europe and written in a script imported from Italy. Our national dish (if one can call it that) of fish and chips was brought over from the Netherlands by Sephardic Jewish immigrants. And as for the British royal family, let's just recall that they changed their name from "Saxe-Coburg" to "Windsor" back in the day and leave it at that.

So other countries would do well to emulate the Museum Siam's openness in celebrating the eclectic origins of their national treasures. And there is a humbling reminder here, that to find a truly indigenous, homegrown culture that’s devoid of any foreign influence, you would have to return to the beginning of human history. And, even then, I have a sneaking suspicion that you’d discover the first Homo sapiens swiped half of their best cave art from the Neanderthals.